Now more than ever, the stories we tell ourselves about who we are and where we thought we came from are under the spotlight.

Now more than ever, the stories we tell ourselves about who we are and where we thought we came from are under the spotlight. Dr. Lindy Brady, Marie Skłodowska Curie COFUND Fellow at the Trinity Long Room Hub, has recently completed a book project entitled Framing History: The Origin Legends of England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

From Hengist and Horsa to Cessair and Brutus, origin myths have been passed down from generation to generation — yet they were not transmitted unchanged. In the medieval period, these stories were used as the basis through which collective identities were formed. These legends show us how medieval peoples believed they arrived to the northwest Atlantic region.

Irish Sea Region

Dr. Brady’s research goes back to the early medieval period to explore the textual and manuscript transmission of origin narratives around the Irish Sea. This will be Dr. Brady’s second monograph. Her first book, Writing the Welsh Borderlands in Anglo-Saxon England, was published by Manchester University Press in 2017 and reprinted in paperback in 2019, when it also won the Best Book on an Anglo-Saxon Topic Publication Prize from the International Society for the Study of Early Medieval England. As a specialist of Old English, medieval Irish and Welsh, Old Norse, and insular Latin languages and texts, she is cognisant that her approach to the Irish Sea Region starts by breaking down traditional siloes between disciplines and language studies. Her research is focused around the challenge of putting these different historical, literary and linguistic traditions in dialogue with one another to reveal how the people of the early medieval Irish Sea Region (the Irish, British, Picts, and Anglo-Saxons) interacted and exchanged knowledge and stories.

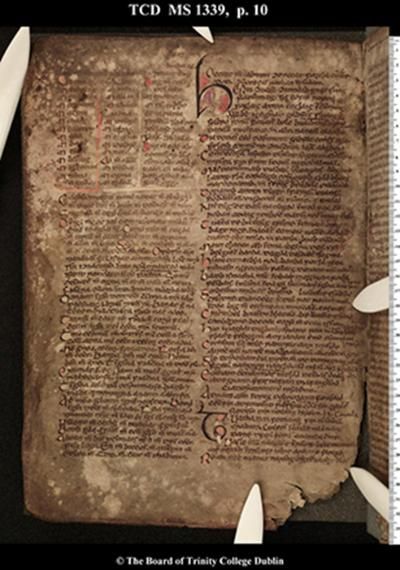

Book of Leinster, MS 1339, Trinity College Dublin.

These texts were not originally written or read in isolation, Dr. Brady argues. That’s why “crossing boundaries” between different languages as well as between literary and historical studies allows her to shed light on the contemporary moment when they were written down. “Individual narratives were in constant development,” Dr. Brady explains, highlighting how they were “written and rewritten to respond to other legends.”

The chroniclers...were interested not only in the origins of their own people but in the origins of everyone in the region.

She recounts that the earliest complete narrative version of the Irish origin myth is found in a Welsh source, while that of the Pictish origin myth is found in an Anglo-Saxon source. “The chroniclers that were collecting these origin myths were interested not only in the origins of their own people but in the origins of everyone in the region, and this corpus of origin myths grew and developed together over time in response to other myths that were being written down about other people.”

Movement and Nationality

While scholars have long understood that origin myths are not an accurate reflection of the past, a popular understanding that origin stories themselves were copied and passed down unchanged through generations still persists. Dr. Brady’s research points towards a much more collective intellectual exercise. Early medieval authors were “reading as many sources as they could get their hands on”, she comments, arguing that the medieval scholars who recorded these origin legends were receptive to external sources of information and“ sought to find answers” about their past.

These myths underscore the presence of what Dr. Brady describes as a “transnational literary community” around the Irish Sea in the early medieval period. They include “narratives of Britons wandering from Troy to an empty island; the Picts ’descent from seven brothers and one sister fleeing Thrace in a boat; waves of Irish settlers sailing (and drowning) on the way from Spain; and Anglo-Saxon mercenaries arriving from the continent.”

...medieval peoples possessed a “collective identity and a connection to a broader world history"...

Dr. Brady argues that these stories and legends reveal that medieval peoples possessed a “collective identity and a connection to a broader world history” and that the origin myths themselves show a focus on movement and strong ties to the continent. The medieval peoples who recorded these myths“ did not want to be defined as a space apart; they saw themselves as holding a tie to some sort of ancestral homeland, both geographically and in terms of having a role in the history of the known world.”

“I hope that Framing History will find audiences both among academics and in a wider community interested in the intellectual and cultural foundations of ‘identity politics’”, Dr. Brady says, adding that the question of where people thought they came from is “often a more interesting question than where they actually came from.”

Fellowship

“It was not the year anyone had planned”, Dr. Brady comments when asked about her fellowship this past year, the last six months of which she spent in lockdown in Dublin in the midst of a global health pandemic.

Despite the ramifications for her research, she had built up an intellectual network of Irish medievalists during the first months of her fellowship, and also counted on the support of early career researchers and colleagues she met at the Trinity Long Room Hub, a community which she said she found “very reassuring during lockdown.”

Her original research proposal had included archival research at Trinity College Dublin, the Royal Irish Academy, and other manuscript repositories. Due to the pandemic, this research will now form part of a follow-on project.

Luckily, Dr. Brady will still be in Dublin for the foreseeable future as she takes up an Ad Astra fellowship in the School of History at University College Dublin. Her project at UCD will be an “outgrowth” of her Trinity Long Room Hub fellowship, adapting the same methodology to encompass a broader study of intellectual networks throughout the early medieval north-west Atlantic region as a whole. Reflecting on her year as a Marie Skłodowska Curie COFUND fellow, she highlights the friendships and support which made it a “productive” and “good work environment” despite the many challenges of the past year.

Dr. Lindy Brady was a Marie Skłodowska Curie COFUND fellow at the Trinity Long Room Hub during the academic year 2019-20. She is an Associate Professor in the Department of English at the University of Mississippi, where she specializes in Old English, medieval Irish and Welsh, Old Norse, and insular Latin languages and texts. Her first book, Writing the Welsh Borderlands in Anglo-Saxon England, was published by Manchester University Press in 2017 and reprinted in paperback in 2019. Dr. Brady has been a Text Technologies Fellow at Stanford University, the A. W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Medieval Studies in the Medieval Institute at the University of Notre Dame, and a British Academy Visiting Fellow at the University of Birmingham.

Listen to Dr Lindy Brady in a virtual 'in conversation' with Dr Immo Warntjes, Ussher Assistant Professor in Early Medieval Irish History (TCD):