Getting a migraine to find megrim

by Agnese Cretella – Food Smart Dublin

Published: 27 August 2020Return to Blog list

Hello followers of Food Smart Dublin! My name is Agnese Cretella and I have joined the amazing Food Smart Dublin project in April this year as the new Postdoctoral social scientist of the team. This blog describes my search for megrim in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was quite an adventure and it left my head aching. But first things first.

My background is in Food Studies and so far, my research focused specifically on urban food governance – a topic I deepened by examining the emergence of food-related social and cultural movements, as well as urban food strategies, policies, ventures, and new urban developments in cities.

I am interested in exploring matters of social and environmental justice around food, in order to improve the sustainability and the wellbeing of both urban and rural communities. In the debate around how to sustainably feed the growing population scholars have diverse perspectives. Generally speaking, the vast majority of the agri-foods literature have tended to focus almost exclusively on terrestrial food production. While there is much to gain from this approach, the scholarly and activists discussion around sustainability have perhaps overlooked the role that seafood can play in contributing to more resilient food systems, enhance food security, community building and increase sustainability by for instance reducing food miles. Of course, seafood has its sustainability issues too, and the increasing anthropogenic pressure on our marine ecosystem must not be overlooked (e.g. overfishing, pollution, ocean acidification). However, our marine environment currently only delivers 2% of human food globally and many resources from the ocean are still untapped. The real value of seafood is not well understood, protected or integrated into global food security and nutrition policy considerations. Therefore, food from the oceans should be a key element in these important debates.

On the one hand, scientists are envisioning Blade Runner scenarios on the future of food, from synthetic meat to hydroponic farms, while we hardly look back to our history as a source of inspiration to eat more locally and more sustainably. Sustainability is certainly a future-focused concept per se, given its strong focus on preserving our resources for future generations. People on the other hand, make their food choices in the present for immediate needs. This is precisely why it is hard to draw consumers into sustainable food choices, because these futures seem too far away from their present.

This is what drew me to join the Food Smart Dublin (FSD) project. Unlike other research projects around sustainable food, FSD brings a unique temporal focus to encourage sustainable consumption: local food history.

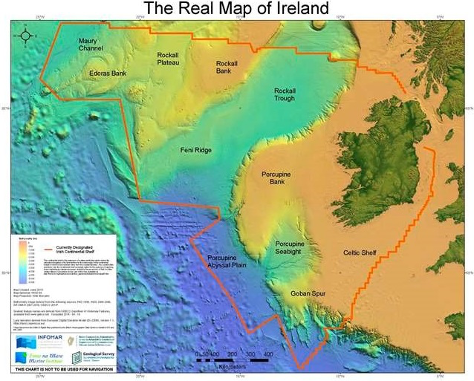

In the case of Ireland this food history is intrinsically linked with its territory: did you know that Ireland’s marine territory is ten times bigger than its terrestrial land mass? Ireland’s seas are the richest in all of Europe and yet the Irish consume very little seafood compared to other countries surrounded by the sea. When the Irish do eat seafood, they mainly eat predatory fish such as salmon, cod or tuna. These sit on the top of the marine food web - much as the lions and tigers on land. This consumption habit is unsustainable and increases the pressure on an already very damaged marine ecosystem with many negative consequences.

If we look into Ireland’s food history, we find that seafood always played an important role in people’s diet, especially for coastal populations. It is evident that a diverse range of fish and shellfish was eaten.

This is a key element that we want to bring back to people’s awareness. We aim to find alternative fish for our historical recipes that might not be as well-known or popular as your salmon or cod but taste equally nice.

One example is Megrim (Lepidorhombus whiffiagonis), the protagonist of our June recipe, a delicious flatfish that I tried to cook myself following the recipe unearthed by FSD from "Mary Cannon's Commonplace Book - an Irish kitchen in the 1700s" and adjusted to the modern taste by Muireann McColgan and Niall Sabongi.

In the current COVID-19 crisis, I temporarily relocated from Dublin to Pescara (which literally means fishy city in Italian), the place where I grew up in Italy. Strategically positioned on the Adriatic coast, I was not too preoccupied about sourcing Megrim while in Italy.

The first problem I encountered however, was with the Italian translation of Megrim.

A bit hopeless, I decided to get in touch directly with my local fishmonger who was super keen on helping to solve the mystery. After sending the Latin name and a picture, he was able to find the correspondent local species of Megrim Sole, called ‘zanchetta’ in vernacular Italian. I purchased three fish to cook a meal for two as I found the Mediterranean megrim to be much smaller than the Atlantic counterpart, but the taste was perfectly good and the meat very delicate.

A few weeks later, I recognised the same fish in a fish stall at the seafood market while on holiday in Syracuse, Sicily but couldn’t get the exact name even this time.

Below you can find the video I made with the Megrim I was able to “catch” at my local fishmonger. Feel free to comment if you have any suggestions on any other translations for Megrim!

All the best,

Agnese