Dr Paul Montgomery's investigation of the fish trap traditions of Thailand’s Andaman Sea coast islands

Author: Paul Montgomery

In 2022-23, Dr Paul Montgomery investigated the fish trap traditions of Thailand’s Andaman Sea coast islands. This research was inspired by some of the work on Indigenous fishing methods from the UNESCO-endorsed Oceans Decade project “Indigenous People, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, and Climate Change: The Iconic Underwater Cultural Heritage of Stone Tidal Weirs” project (1).

Thailand’s Andaman coastal islands are home to small small-scale fishing practices, including fish traps, hook-and-line, dive-fishing, and gill net fisheries, which form a substantial part of the activities of the island’s inhabitants (2). One of the most common is the number of wood fish traps used for fishing in the reef environments. These fishing traditions represent a mixture of complex cultural traditions and subsistence strategies, exemplifying how communities across the Asia-Pacific have interacted with the marine environment and evolved their methods and technology to utilize marine resources (3). In parallel, the local economy has also undergone a transformation during the last 20 years as tourism (especially ecotourism eco-tourism) has become more critical.

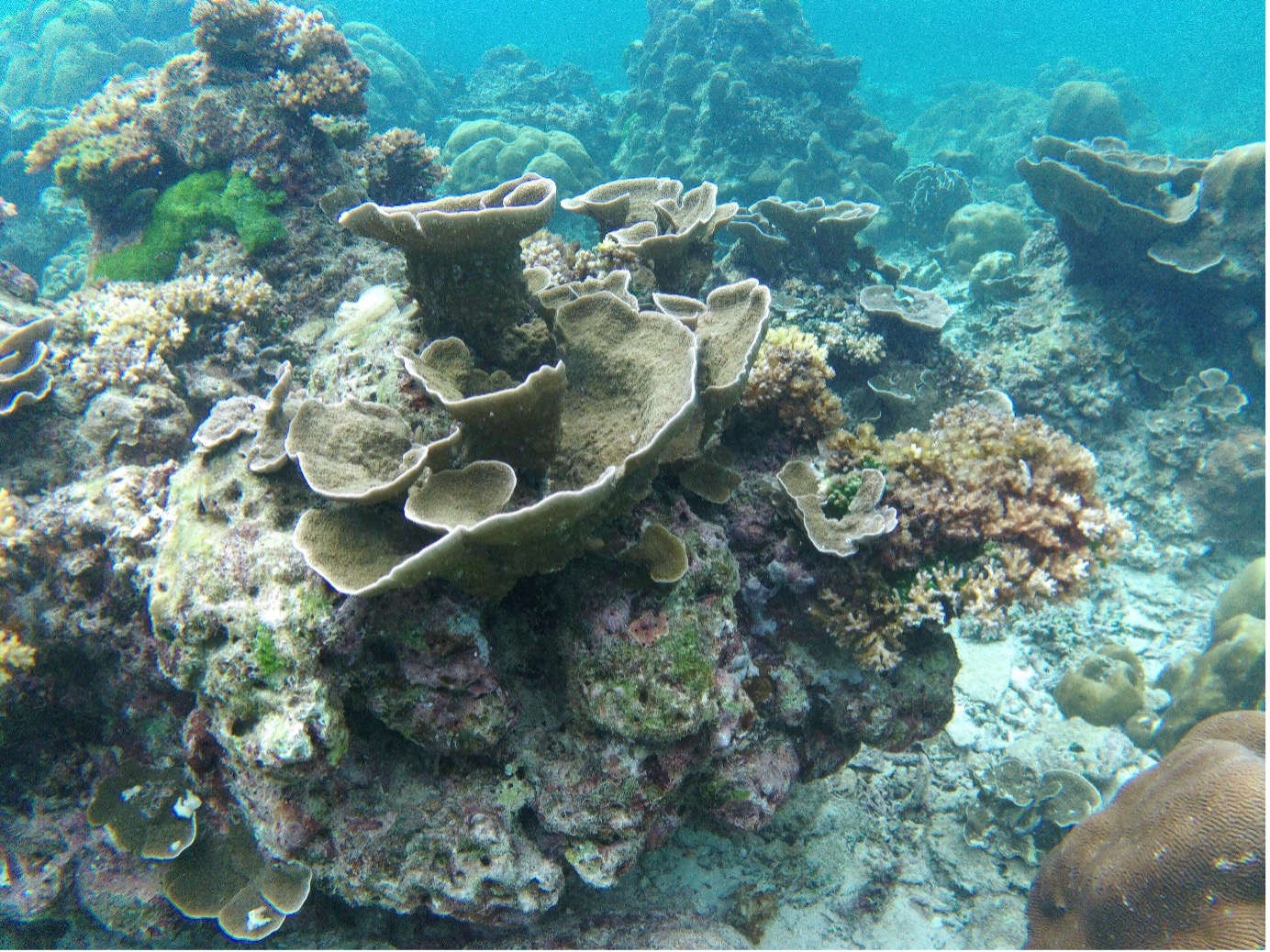

Historically, the island's location on the Andaman Sea has made it a gateway through which multiple historical actors and empires have left their mark. These islands are home to a mixed population of ethnic Thai Buddhists, Thai-Chinese, Muslims, and indigenous peoples (including ethnic groups, Moken/Moklen, Urak or Lawoi, to as "Sea Gypsies" (chao leh in Thai) (4). In terms of biodiversity, especially marine biodiversity, the wider Andaman encompasses a wide variety of different ecological zones (such as mangrove forests, coastal rainforests, and offshore islands), in particular a large number of coral ecosystems that support a range of fisheries, both artisanal and industrial. There are 13 Marine National Parks along the Andaman Sea coast containing major coral reefs (Figure 1.). These marine ecosystems are deeply linked with artisanal fish trap fisheries. They are a vital part of the economy of coastal communities and are still vitally important economically and culturally today. Trap fishing is focused on catching high-value fish like groupers (Epinephelus malabaricus and Epinephelus quoyanus), snappers (Lutjanus argentimaculatus), and emperor (Lethrinus lentjan) with bycatch like parrotfish (Scarus ghobban) and goatfish (Upeneus tragula) being taken also (5).

Andaman fish traps

During fieldwork in the region, many different types and forms of fish traps were observed being constructed and used by fishing communities (figure 3). The two most common types are rectangular (3/4m long) and barrel-shaped (1/2m long), called "Lob or Saiyai" fish traps that are constructed from wood such as mangroves, rattan, nets, and metal wire. These traps are built using long flexible branches traditionally bound together with a cord, but in the modern era, metal wires are used as fixings. The assembly of the traps begins with constructing a square, which forms the basin frame for the traps regardless of their size. Onto the frame, three or four branches are bent over from one side to the other, forming an arch over which the nets or chicken wire is laid on top, forming the housing of the trap. At the mouth of the trap, two small u-shaped branches form a double chevron shape in between which the trap entrance a funnel is constructed. The funnel allows fish to swim into the frame, preventing their exit. Being constructed primarily of wood, the trap is relatively buoyant, and it is necessary for stone weights sourced from the beach or garden to be fixed to the side of the trap, usually laid on top of the wire housing.

The other common type of trap (see figure 4), which is observed being utilized, is commonly referred to as the Bubo/Bubo trap Philippines, a kind of bamboo fish trap that is found across Southeast Asia as far as way as the coast of eastern Africa (6). This type of trap is constructed by an intricate matrix of pieces of dried bamboo that are overlapped and intertwined in a mesh pattern, which forms the structure of the trap walls, traditionally the outer layers of the bamboo, which are much more durable and last longer. Stones are usually fixed to the trap's inside to give it weight, enable it to sink to the seabed, and prevent the local currents from washing it away.

Conventional forms of fish traps usually involve pieces of bait, such as old or rotten fish, being placed inside the trap to attract other fish. However, in the case of some of these traps, vegetation, such as branches and sticks, was placed on top of the trap to form a sheltered environment that was attractive to fish, enticing them to enter the trap. This method of creating an inviting environment that's shaded and appears to be safer than swimming in open water is a method of fishing observed in other fish trap traditions. Such traps must be left on the seabed for up to two weeks for the fish to inhabit them.

One of the more interesting components of this type of fishing is the local traditional knowledge that the fishermen who operate this type of fishery acquire over generations. Traps were deployed joined by a rope or hand; they are traditionally dropped over the side of a boat by the fishermen who do not mark their traps with buoys but rather by dead reckoning of landmarks on shore to help them locate the trap. These types of traps have been known to be used in depths ranging from 20-100 meters of water. The traps are retrieved via a long bamboo pole with a hook at the end used to latch onto the trap or the linked rope between them.

The construction and deployment of these traps is a tradition passed from person to person down generations of fishing communities along these coastlines. Traditionally, there are no diagrams or written instructions for constructing these traps; rather, they are learning through trial and error, mimicking other traps built by more experienced fishermen in the community. A deep understanding of the marine environment is gathered to enable them to choose the best time to set their traps and where they can catch fish or particular species. As with all fishermen worldwide, they're naturally cautious about sharing the locations of some of their fishing spots, which are never divulged to anyone. Despite being only a tiny fraction of the number of fish caught in the region, this fishing tradition is vital to the local indigenous communities as part of their livelihood. With the growth of tourism, the possibilities have grown for fishermen to make a living from more than fishing. However, they face a dichotomy regarding the inherent risks of overfishing and damaging the local ecology.

Bibliography (MLA)