Trinity College Library Dublin Acquires Largest Collection of Samuel Beckett Letters Ever Offered for Public Sale

Posted on: 09 October 2014

Trinity College Library Dublin has just purchased the most extensive collection of Samuel Beckett letters (347 in number) ever to have been offered for public sale. It now holds the largest collection of Beckett letters of any research library in the world. It is a fitting home for the correspondence of one of Trinity College Dublin’s most famous alumni.

These letters and cards were sent from the Nobel prize-winning author to artists Henri and Josette Hayden. Beckett and his wife, Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, met the Haydens when both couples were in southern France evading discovery by the Nazis during the Second World War. The letters in this collection begin in 1947 and cover the difficult period in Beckett’s life during which his mother and his beloved brother Frank died. They also cover the most intensely fertile period of his writing life when he was completing Waiting for Godot, and working on all three books of his trilogy Molloy, Malone dies and The Unnameable. There is much for the biographer in this new cache but even more for the student of Beckett’s literary work.

This latest acquisition cements Trinity College Library’s position as the world’s number one repository for the correspondence of Samuel Beckett. Key among the other collections in Trinity are the letters Beckett sent to his friend the poet Thomas MacGreevy and those he sent to translator and literary critic Barbara Bray. In the MacGreevy collection Beckett wrote in a most personal manner; in the Bray collection he wrote principally about his work. The Hayden collection links these two correspondences both by overlapping chronologically and also in being a combination of the personal and the literary. Thus they allow scholars to see the different ways in which Beckett expressed himself to different people; they cover the time when Beckett made his final break from Ireland after his mother’s death, and also the period of his first significant literary success.

When the recent volume of Beckett’s published letters by Cambridge University Press appeared, the editors noted with some regret that while they had built up a “substantial corpus” of his correspondence, it was by no means complete, adding that: “By far the most important collection to which the editors have not had access is constituted by the more than 300 letters addressed to Josette and Henri Hayden,” which, they note, were in private hands. No longer: they are now in our hands, here in Trinity, where they will be available to a new generation of scholars.

There is something very fitting about the manner of the arrival of these materials to the Library. Trinity was able to make the purchase thanks to the generosity of a former staff member: William O’Sullivan, Keeper of Manuscripts in Trinity from the 1950s to 1982, left a bequest to the Library which made this acquisition possible. It is this same kind of practical benevolence that Samuel Beckett displayed towards Trinity College of which he is the most famous 20th-century graduate. He presented some of his own literary manuscripts to Trinity’s Library in the 1960s; he gave some of his Nobel prize money to the Library; he also gave a year’s worth of royalties from the Broadway production of Krapp’s Last Tape to the Berkeley Library’s building fund in the 1950s.

This generosity characterised Beckett’s dealings with his friends. In the case of Henri Hayden, as these letters reveal, Beckett’s assistance ranged from buying paints for him to introducing the artist to the dealer Victor Waddington, thereby securing Hayden’s reputation in the art world. When Henri became ill in his eighties the practical nature of Beckett’s friendship became even more important: he sorted out the couple’s taxes and ensured their rent was paid.

![Ussy, 3 Aug 1955, [self-portrait by Gerard Dou]. "Thanks for your nice card. I have a bad feeling about London. But that’s the least of my worries. Best wishes, Sam."](https://tcdie-cms01-production.terminalfour.net/manual-upload/wp-content/uploads/archive/1412847347_photo_2__ms_11488-vol_1-62_resized.jpg)

“These Beckett letters are very significant for Beckett scholarship at Trinity College, as well as nationally and internationally. We have been developing collections of significant Irish creative writers, and these letters build on the existing Beckett collections the Library already holds. We welcome the opportunity to be able to share these collections with students of Beckett and researchers across the globe. To mark its arrival, we have mounted a small exhibition in the Long Room for those who would like to view this precious correspondence. We intend to make it more widely accessible for scholars and for the general public in the future,” said The Librarian and College Archivist, Helen Shenton.

The Hayden collection follows the acquisition this year of several drafts of Beckett’s work Ohio Impromptu from the Beckett scholar, Stanley E. Gontarski. Also in this new acquisition is Gontarski’s correspondence with Beckett from 1972; a copy of Three Plays (1984) revised by Beckett; and the proofs of Gontarski’s critical edition of Endgame, heavily revised and annotated by himself, Beckett and Beckett’s biographer James Knowlson.

Extracts from Hayden Collection of Letters and relationship with Samuel Beckett’s Literary Works

To Henri and Josette Hayden, Foxrock, Dublin, August 1950

“My mother is still declining. It’s like one of those decrescendos made by the trains at Ussy which I used to listen to at night, interminable, suddenly resuming just when everything seemed finished and the silence final. I think she will die in hospital in a week or so.”

[This is a remarkable letter; what Beckett is describing is the shape of listening to his mother’s last days – a shape that will be used again and again, in works such as Rockaby.]

****

Postcard from Ussy, August, 1955;

Painting by Gerard Dou, Portrait of the Artist from the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam; 1613-1675

[There are a great many picture postcards in the collection. Beckett may have communicated with the Haydens – a painter and a designer – partly through images. Some are of stunningly banal scenes – a nondescript stretch of canal or street, or an empty field; others, however, are paintings. This image may be a pre-figure to Krapp’s Last Tape, written shortly after.]

****

Paris, September, 9th, 1963

To Henri Hayden [during production of Happy Days]

“Madeleine rather lacks substance and gravitas. We’re trying to infuse her with some. She has a kind of irrepressible vivacity. That’s not what Winnie’s smile is about.”

[The letters – particularly those from the 1960s and 1970s – give a vivid sense of Beckett as a person of the theatre, working with actors, directors and producers. ]

****

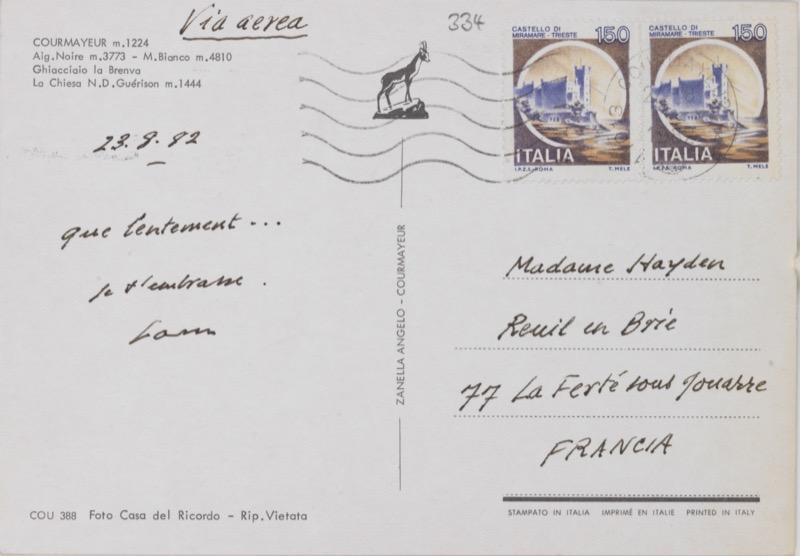

To JH, August 23rd, 1982

Que lentement …

Love

Sam

[This late letter, made up of only two words, seems like a complete late work in its own right.]

Samuel Beckett and Trinity College Dublin

Samuel Beckett entered Trinity College in 1923 aged seventeen years. He specialised in French and Italian and graduated in 1927. While he was in College he represented the College in cricket.

Beckett was expected to continue in an academic career and was appointed assistant lecturer in French literature in Trinity in 1930. He disliked teaching, principally because, at this time, he was becoming more determined to become a writer.

Beckett always showed himself a friend to Trinity College Library Dublin. In 1959 the Library embarked upon a fundraising campaign to build what is now the Berkeley Library. Beckett was asked to write a play with a Library theme to assist with the campaign. He agreed to attempt it but, as he expected, could not comply: instead he granted the royalties from a year’s productions of Krapp’s Last Tape to the campaign.

The foundations for the Library’s internationally-renowned collection of Beckett manuscripts were laid in 1969 when the author generously presented four literary notebooks to Trinity College Library. These notebooks contain drafts of works, translations and abandoned prose and drama. One of the notebooks contains a fragment of Beckett’s novel Malone meurt/Malone Dies and another contains a significant amount of the radio play Embers.

The Library has continued to build on this collection; the key strength is in correspondence. The letters from Beckett to his good friend the poet Thomas MacGreevy are unusual in being so open; they show Beckett, as a young man and a young artist, writing frankly to a close friend. There is also a large collection of letters to his friend the theatre director Barbara Bray.

One of the major literary pieces in the collection is a notebook in which Beckett started writing what became his late great work Imagination dead imagine. Trinity College Library also holds the first edition of Waiting for Godot which was used in the rehearsal for the first performance of the play.

The Samuel Beckett Estate has also shown support to the Library in presenting the notes Beckett took on the subject of philosophy and literature after he left College.

Apart from the manuscripts, the Library’s Department of Early Printed Books has a full collection of Beckett’s published works and an impressive range of published scholarship.