Inflammation Stops The Clock

Posted on: 18 May 2015

Researchers at Trinity College Dublin and the University of Pennsylvania have uncovered an important link between our body clock and the immune system that will have relevance to the treatment of inflammatory and infectious diseases.

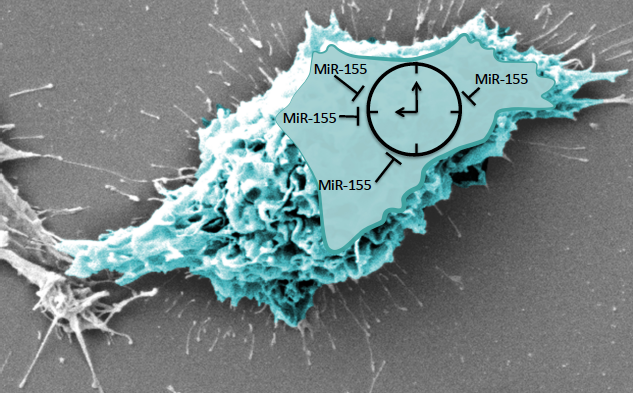

Their study, published this week in leading international peer-reviewed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, shows how the biological clocks inside important white blood cells (called macrophages) stop when they are exposed to bacteria. Crucially, stopping the clock allows the cells to become active and inflamed.

The complex mechanism involves a factor called miR155, which destroys a key cog in the clock’s mechanism called BMAL1. This allows the macrophage to make a number of inflammatory proteins that effectively wake up and activate the immune system.

Explaining the mechanism, Senior Research Fellow in the School of Biochemistry and Immunology at Trinity, Dr Annie Curtis, who is a lead author of the paper, said: “It’s as if an infection causes the alarm in a macrophage clock to go off.”

Scientists have known for a long time that the immune system and body clock are interconnected, and that our immune system responds differently to bacteria depending on the time of day at which it is exposed. For example, in mice and humans, the immune response tends to be greater at the beginning of the night compared to the early morning.

The researchers found that this was dependent on the level of clock protein (BMAL1) present in the macrophage. BMAL1 functions as a ‘dampener’ of the immune system and, because levels are lower at night, the immune system can be more active.

Why this is the case is not fully clear, but a less active immune system during the day (when BMAL1 levels are higher) might mean that our bodies don’t over-react to infections, which are more likely to occur when we are active and meeting sources of infection. However, if our systems need to mount a big response – such as when we are infected with a virus or bacteria – then macrophages can reduce BMAL1 levels, and they do this via miR-155.

“This was a big piece of the puzzle – we knew that uncovering what causes the reduction in BMAL1 within activated macrophages would be important to link the immune and clock system together,” said Professor of Biochemistry at Trinity, Luke O’Neill, who is joint-senior author on the study.

The researchers also showed that miR-155 induction is greater in the evening than in the morning, providing rationale as to why our immune response is more active at the transition into night.

“There may be times such as during an acute infection where it's advantageous for the immune system to use miR-155 to stop the macrophage clock and allow the body to clear the infection,” said Professor Garret FitzGerald, from the University of Pennsylvania, who is a joint-senior author. However, he added: “When inflammation is present for long periods of time, as is the case for patients with a chronic disease like rheumatoid arthritis, this constant targeting of the clock may actually worsen disease.”

Taken together this study underlines the important role of the body clock in our immune response and provides a rationale for treating immune disorders at certain times of the day and using therapies that restore the clock as anti-inflammatory agents.

“It may even help us target cancers by adjusting the time we administer cancer immunotherapies to coincide with this daily rise and fall in the activity of our immune systems,” added Dr Curtis.

This work was supported by grants from the European Research Council, Science Foundation Ireland and the National Institutes of Health.