ADHD Medication

Medication does not cure ADHD, but can be a highly effective way to treat the symptoms of ADHD when it is taken as prescribed. It is important to note that none of the treatments for ADHD will cure the condition and so ongoing care and treatment monitoring are important. The type or extent of treatment is likely to change over time as children mature.

Though not a cure, medication treatment does allow the child, adolescent, or adult to better function and manage their ADHD. It allows them to benefit from interventions intended to improve their overall functioning in school, at home, at work, and in the community. A percentage of children may no longer require treatment as they grow into late adolescence and adulthood.

As a parent you may have been told about stimulant drugs such as methylphenidate (Ritalin) and dexamphetamine which have been prescribed for children with ADHD since the 1930s.

It may seem strange to prescribe a stimulant medication to a child who is overactive. However medications like Ritalin work by stimulating those parts of the brain that control behaviour and regulate activity. The medication helps many children to concentrate and regain control over their actions.

Many parents have commented on the dramatic improvements which can occur with medication for ADHD. As children calm down they may be better able to mix with their peers. They can also respond more effectively to their teachers and parents. Children may become less aggressive as well as less hyperactive. Their performance at school may improve significantly.

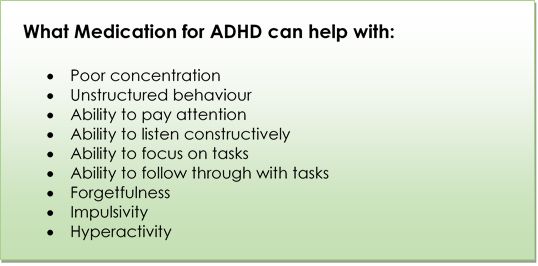

It is important to note that ADHD medication targets the core symptoms of ADHD; inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity. Medication may also help to reduce irritability / emotional dysregulation. It will not directly treat any of the other disorders commonly associated with ADHD, such as Oppositional Defiant Disorder / Conduct Disorder / anxiety disorders / learning difficulties. However when a young person’s symptoms of ADHD are well treated, it is likely that they will be better able to engage in behavioural strategies / learning support to help with these other conditions.

- Stimulant medicines

- Non stimulant medication

There are two types of medication available for ADHD; stimulants and non-stimulants.

Stimulant medicines

Research studies have shown that stimulant medicines are the most effective treatments for ADHD. They have been available for decades and have been very well studied. Research has shown that stimulants are quite safe when prescribed to healthy young people, and used under medical supervison.

There are two stimulants available in Ireland – Methylphenidate and Lisdexamphetamine. These medicines work by regulating the young person’s own brain chemicals, in particular the chemicals Dopamine and Noradrenaline.

Methylphenidate is the most commonly used medication. There are several formulations of methylphenidate that are licensed in Ireland.

- Immediate release Methylphenidate (Medikinet IR or Ritalin IR) – Lasts for 4 hours

- Modified (slow) release Methylphenidate (Medikinet MR / Equasym XL / Concerta XL) – Lasts between 8 and 12 hours depending on the formulation.

Lisdexamphetamine is also a stimulant and is similar to Methylphenidate. It is typically used as a second line medication when Methylphenidate fails to work or causes side effects. The trade name in Ireland is Tyvense. This medication lasts about 10 hours.

Non stimulant medication

There is another class of ADHD medication referred to as “non-stimulants”. These medications may be good alternatives for children who do not respond well to stimulant medication, cannot tolerate the side effects of stimulant medications, or have other conditions along with ADHD.

Atomoxetine (“Strattera”) is a non-stimulant. It is usually chosen as a second or third line medication. It has a 24 hour duration of action and this medication may be suitable for young people who have ADHD and tics, or if stimulants cause problematic side effects for the young person.

Guanfacine (“Intuniv”) is another non stimulant medication that is effective in ADHD. Recent studies have suggested that this medication may also be helpful in reducing oppositional behaviour that is associated with ADHD.

As with any medication there are possible side effects. Detailed information leaflets on each medication used in ADHD are provided to parents before starting treatment, and the clinician will discuss the medication in detail.

Common side effects

Stimulant medication:

The commonest side effects of stimulant medications are listed below.

- Loss of appetite can lead to weight loss and could potentially slow growth. This can be helped by giving the medication after food and encouraging your child to eat in the evenings after the medication has worn off. Your child’s height and weight will be monitored closely by your clinician

- Difficulty in settling to sleep can be a problem. This is more likely if the stimulant medication is given later in the day.

- Headaches, abdominal pain and sickness are occasionally a problem when first starting on the medication but usually settles in a couple of days.

- Anxiety and mood swings may be a problem. If these are significant and continue beyond the first week of commencing medication you should contact your clinician as this type of medication may not be suitable for your child.

- Tics may get worse or may start with the medication. You should contact your clinician to discuss as a different medication may be more suitable.

- ‘Rebound’ symptoms of ADHD when the medication wears off in the evening. The medication schedule can be adjusted so that it is not wearing off during a time of high demand e.g. homework time.

- Skin rashes may occur occasionally.

- Small changes in heart rate and blood pressure are common and not significant. Palpitations or chest pain are rare but you should contact your clinician straight away and medication may be stopped. Your child’s blood pressure and pulse will be checked at each appointment.

Less common are

- itching

- changes in appetite and weight

- depression

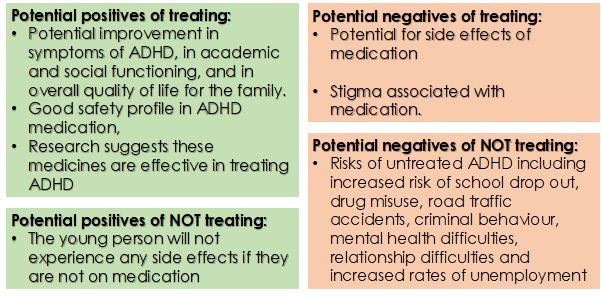

It is always an important decision to start medication and must be carefully considered.

Your decision about medication is not written in stone – a different decision might be made at another time. It is important to note that medications are started on a trial basis – therefore parents will have the opportunity to base their decisions about medication on pros/cons they actually see. Changes in medication or in dose are informed by reviewing the balance between positives and negatives.

Your treating doctor or specialist nurse will help you weigh up the potential benefits and negatives of starting medication. You can compare these with the pros and cons of not starting medication.

Parents often ask “What are the risks of not treating ADHD?”. There has been much research investigating this and many studies have looked at different aspects of this.

Some facts about untreated ADHD that have been reported in different studies are listed below:

- Untreated ADHD is associated with increased rates of unemployment (Halmoy et al, 2009) and sickness absence (de Graaf et al, 2008)

- There are clear associations between untreated ADHD and illicit drug use and alcohol addiction (Kaye et al, 2013, Langley et al, 2010, Manuzza et al, 2008). This may be because if ADHD is left untreated, adolescents are more likely to self medicate. The sequence generally begins with tobacco and alcohol, then may turn to cannabis, then possibly to cocaine or other drugs.

- Lack of academic achievement in young people with untreated ADHD has been reported in a number of studies. One study found that 28% of young people with ADHD repeated a year in school compared with only 7% of the general population (Fried et al, 2013). Another study reported that adolescents with ADHD were less likely to graduate from high school and less likely to complete a college degree (Biedermann et al, 2006).

- Serious antisocial behaviour and involvement with the police have been associated with untreated ADHD (Langley et al, 2010, Manuzza et al, 2008)

- In a study that looked specifically at the difference between adults who had treated versus untreated ADHD, those with untreated ADHD were 8 times more likely to have adjustment disorder, 4 times more likely to have depression and generalised anxiety disorder and twice as likely to have sleep disorders (Tsai et al, 2019).

- Untreated ADHD can have a detrimental effect on the relatives of patients and their carers (Cadman et al, 2012).

- There is a significantly increased risk of teenage pregnancy in young people with ADHD. One study found teenage pregnancy in 15% of young women with ADHD compared with 3% without (Skoglund et al, 2019), and another reported that girls aged 12-16 with ADHD were 4 times more likely to become pregnant, while boys the same age were 2.5 times more likely than their non ADHD peers to become parents (Østergaard et al, 2017)

- Young adults with ADHD are over three times more at risk of a sexually transmitted disease compared with those without ADHD, and treatment of ADHD reduces this risk (Chen et al, 2018).

Deciding which medicine is right for a young person takes time, because doctors / specialist nurses may have to try more than one medicine to find the one that works the best. Some ADHD medicines may not be right for a young person because they cause side effects that are unpleasant, or because they do not fully treat the ADHD symptoms.

Parent and teacher monitoring of positive and negative effects will increase the chances of learning about which medication is best for a young person, at what dose, and whether medications should be used alone, or in combination with one another.

A medication’s side effects can usually be managed by reducing the dose, changing the type of medicine (e.g., a shorter acting medicine), altering the time it is taken, or switching to another medication.

Generally the clinician will typically start with a low dose of stimulant medication (Methylphenidate) and increase the dose over a period of weeks until the ADHD symptoms are under control. It can take several weeks to find the best medication and optimal dose for your child. Studies indicate that over three-quarters of young people will respond to such adjustments when a second type of stimulant medication is used if the first one is not satisfactory.

At the start of medication treatment and during increase in medication dose, parents and teachers will be asked to complete rating scales that provide information about ADHD symptoms and about other symptoms that could occur as side effects of the medication.

This information can be used by your clinician to determine the correct medication and dosage and monitor how the young person is doing. The parent and young person will attend the clinic regularly while medication is being adjusted.

https://www.tcd.ie/medicine/psychiatry/research/adhd/resources/

Response to stimulants can be seen very quickly – within 30 to 90 minutes. The results can be quite dramatic in young people with hyperactivity and impulsivity, but are typically less obvious in those with attention problems. Typically medication is started at a very low dose to minimise side effects, and a response may only be seen when the medication dose is increased to a particular level.

With a non-stimulant it often takes at least a couple of weeks for response to be seen, and it can take up to 12 weeks for the full effects to be observed.

Sometimes, the pharmacy will dispense a medicine with the same “generic” name but a different trade name. Clinicians will prescribe a particular brand of medication and parents should ensure that the name written on the prescription matches what is given by the pharmacy. This is because there are subtle differences between the different formulations of these medicines, and some young people respond well to one formulation but not to another, or may have side effects on one formulation but not on another.

The prescribing clinician knows about the differences in formulations and will try different versions of the same medicine for a young person to investigate what suits best, so it is important that what is prescribed is exactly what is taken.

Most medication for ADHD is taken once a day, in the morning after breakfast. Sometimes a second dose of stimulant medication may be prescribed in the late afternoon. Guanfacine (“Intuniv”) is started at night time as it can cause drowsiness, however this side effect generally wears off after a couple of weeks, and then this medicine can also be taken in the morning.

Some young people may find it difficult to swallow tablets, but some of the ADHD medications can be sprinkled (e.g., on apple puree / soft breakfast cereal like porridge / Weetabix) or dissolved. Most young people can learn quickly to swallow tablets, and this is an important skill for life. There are numerous online videos about swallowing tablets.

Medication for ADHD should kept in a locked cupboard and an adult should administer the medication to the young person. Any unused medication should be returned to the pharmacy for disposal.

When starting medication there will generally be a number of reviews over the first 2-3 months to optimise the medication type and dose. Once the medication dose is optimised, the young person will only be required to attend every 3 months (<10 years) and every 6 months (>10 years).

Physical monitoring (height, weight, blood pressure and heart rate) will be measured in accordance with international guidelines during clinic visits.

Clinicians have often recommended or agreed to parent requests that young people can take a break from their ADHD stimulant medication on weekends, holiday and during the summer.

However it is important to consider the reasons for taking a break from medication. Stimulant medication can help the young person to complete homework, participate in extracurricular activities, pay attention while driving and possibly may help teens resist engaging in cigarette smoking, substance use, and risky behaviour. If the young person is tolerating medication well, and has more severe ADHD symptoms, the clinician is likely to recommend staying on ADHD medication full-time without breaks.

It is however possible to reduce dose or take breaks from stimulant medication, and if a parent feels that this is important for the young person for any reason it should be discussed with their clinician.

Taking a break from non-stimulants is not as easy as from the stimulant medications. Non-stimulants often need to be taken daily for a period of time before benefit can be achieved; missing doses may undermine benefits and may also result in withdrawal effects.

About 60% of young people diagnosed with ADHD will continue to have problems with one or more symptoms of this condition later in life. In these cases, ADHD medication can be required for longer periods of time.

However, as a young person matures, parents or teachers may notice signs that suggest that they might be able to reduce or stop ADHD medication:

If the young person is :

- Symptom-free for more than a year while on medication

- Doing better and better, but on the same dose of medication

- Showing appropriate behaviour despite missing a dose or two

- Showing a newfound ability to concentrate.

then it is time to speak to your child’s clinician about re-evaluating his or her medication dose.

As children grow into adolescence, many factors may lead them to demand a stop to their medication. The choice to stop taking ADHD medication should be discussed with the prescribing clinician, family members, possibly teachers, and the young person.

It is important that the young person has a good understanding of the risks of stopping ADHD medication. If medication is stopped, parents should monitor behaviour as closely as possible, and consider re-starting again if academic performance falls behind, or if risk taking behaviours emerge.

It is important that you and your child discuss what ADHD is and how medication will help them, why it is being prescribed, and how it affects their ability to function. This recommendation is especially true for older children and adolescents who may have concerns about being “different” because they are taking medicine. You can talk to your child about this, and you can compare taking ADHD medications to wearing eyeglasses. Wearing glasses helps you to see better just as ADHD medication helps you to focus on your work, pay attention, learn, and behave better.

Young people with ADHD and their parents often report that they find certain books, articles or websites helpful. You will find a list of resources here.

The information on this website was compiled by the HSE ADMiRE team and ADHD research group in Trinity College Dublin, and was partially based on the following publications / websites:

- “Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder – Information Booklet for Parents”. Compiled by members of the St. James’/ Clondalkin Multidisciplinary CAMHS Team

- “Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Information Pack for Parents”. NHS Tayside, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service, Perth.

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry and American Psychiatric Association ADHD: Parents Medication Guide.

- ADHD Ireland website https://adhdireland.ie/

- The National Attention Deficit Disorder Information and Support Service (ADDISS) Website http://www.addiss.co.uk/

Publications

- Biederman, J., Faraone, S., Spencer, T., Mick, E., Monuteaux, M. & Aleardi, M. J. J. C. P. (2006). Functional impairments in adults with self-reports of diagnosed ADHD. 67, 524-540.

- Cadman, T., Eklund, H., Howley, D., Hayward, H., Clarke, H., Findon, J., Xenitidis, K., Murphy, D., Asherson, P., Glaser, K. J. J. o. t. A. A. o. C. & Psychiatry, A. (2012). Caregiver burden as people with autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder transition into adolescence and adulthood in the United Kingdom. 51, 879-888.

- Chen, M.-H., Hsu, J.-W., Huang, K.-L., Bai, Y.-M., Ko, N.-Y., Su, T.-P., Li, C.-T., Lin, W.-C., Tsai, S.-J., Pan, T.-L. J. J. o. t. A. A. o. C. & Psychiatry, A. (2018). Sexually transmitted infection among adolescents and young adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide longitudinal study. 57, 48-53.

- De Graaf, R., Kessler, R. C., Fayyad, J., ten Have, M., Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M., Borges, G., Demyttenaere, K., Gasquet, I., de Girolamo, G. J. O. & medicine, e. (2008). The prevalence and effects of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on the performance of workers: results from the WHO World Mental Health Survey Initiative. 65, 835-842.

- Fried, R., Petty, C., Faraone, S. V., Hyder, L. L., Day, H. & Biederman, J. J. J. o. a. d. (2016). Is ADHD a risk factor for high school dropout? A controlled study. 20, 383-389.

- Halmøy, A., Fasmer, O. B., Gillberg, C. & Haavik, J. J. J. o. a. d. (2009). Occupational outcome in adult ADHD: impact of symptom profile, comorbid psychiatric problems, and treatment: a cross-sectional study of 414 clinically diagnosed adult ADHD patients. 13, 175-187.

- Kaye, S., Darke, S. & Torok, M. J. A. (2013). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among illicit psychostimulant users: a hidden disorder? 108, 923-931.

- Langley, K., Fowler, T., Ford, T., Thapar, A. K., Van Den Bree, M., Harold, G., Owen, M. J., O'Donovan, M. C. & Thapar, A. J. T. B. J. o. P. (2010). Adolescent clinical outcomes for young people with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. 196, 235-240.

- Mannuzza, S., Klein, R. G., Truong, N. L., Moulton III, P. D., John L, Roizen, E. R., Howell, K. H. & Castellanos, F. X. J. A. J. o. P. (2008). Age of methylphenidate treatment initiation in children with ADHD and later substance abuse: prospective follow-up into adulthood. 165, 604-609.

- Østergaard, S. D., Dalsgaard, S., Faraone, S. V., Munk-Olsen, T. & Laursen, T. M. (2017). Teenage parenthood and birth rates for individuals with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry 56, 578-584. e3.

- Skoglund, C., Kallner, H. K., Skalkidou, A., Wikström, A.-K., Lundin, C., Hesselman, S., Wikman, A. & Poromaa, I. S. J. J. n. o. (2019). Association of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder With Teenage Birth Among Women and Girls in Sweden. 2, e1912463-e1912463.

- Tsai, F.-J., Tseng, W.-L., Yang, L.-K. & Gau, S. S.-F. J. P. o. (2019). Psychiatric comorbid patterns in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: Treatment effect and subtypes. 14.

- Wymbs, B. T., Pelham Jr, W. E., Molina, B. S., Gnagy, E. M., Wilson, T. K., Greenhouse, J. B. J. J. o. c. & psychology, c. (2008). Rate and predictors of divorce among parents of youths with ADHD. 76, 735.