Education is great for your health in many ways. Should education be free?

“Investment in education is investment in health” – Provost Linda Doyle, December 2021

Authors: Eleanor Colreavy & Martina Mullin

One of the most important things you can do for your health is engage in further education – that’s any type of post-secondary school education, be it apprenticeships, certificate, degrees etc. We’re delighted to have you in Trinity and though you will find Trinity tough in many ways, being here is a great investment, not just in your future health and longevity, but in the future health of your children if you have them.

One of the most important things you can do for your health is engage in further education – that’s any type of post-secondary school education, be it apprenticeships, certificate, degrees etc. We’re delighted to have you in Trinity and though you will find Trinity tough in many ways, being here is a great investment, not just in your future health and longevity, but in the future health of your children if you have them.

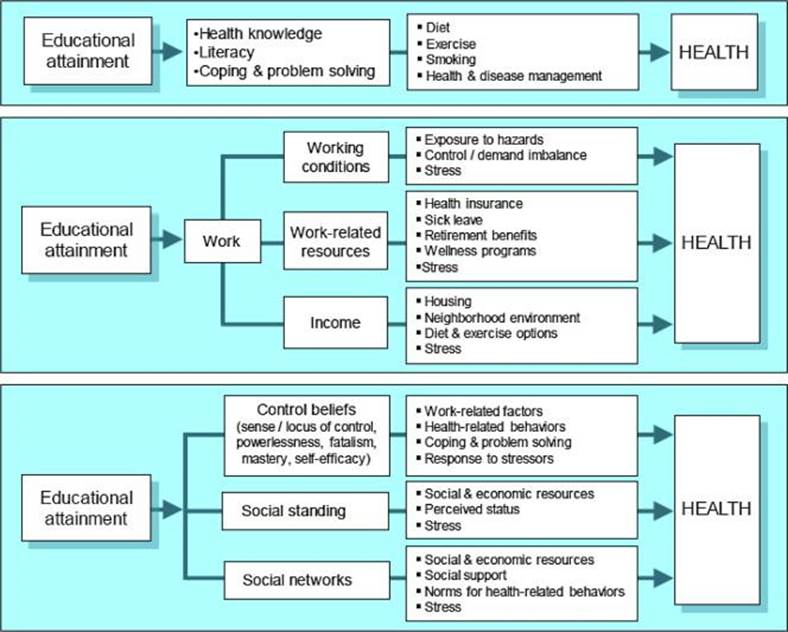

We love this model from 20111 which shows how education works its magic on health. We hope that you can think of the challenges you face in Trinity as worth the stress and difficultly because of the long term benefits you’ll gain.

We think third level education should be free, as it almost was in Ireland in the 1990s. If you agree, you might consider working with us to become more politically active to encourage more investment in education. You can check how to get involved here.

Education and Social & Psychological Factors

Believing you have control is linked with improved health outcomes and education is associated with better perceived control.

Education is a catalyst for profound changes in our social, psychological, and physical well-being. Research has shown that education is linked with social and psychological factors, including perceived control, social status, and social support. 1

Education is a catalyst for profound changes in our social, psychological, and physical well-being. Research has shown that education is linked with social and psychological factors, including perceived control, social status, and social support. 1

Education helps you feel in control

Higher levels of education are linked with a stronger sense of personal control, fuelled by opportunities for employment and income provided to you by your education. This enhanced sense of control empowers you to navigate life's challenges with confidence, persistence, and problem-solving skills. Positive beliefs about your personal control are linked with improved health outcomes, including reduced physical impairment, decreased risk of chronic conditions, and health-related behaviours such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. 2,3

Education gives status - and that matters

Education is associated with higher social standing – and status is consistently linked with better health outcomes.4

Experts have long emphasized the role of social status, i.e., an individual’s rank or position within society, in linking education with health. Alongside income and occupation, education plays a significant role in determining where you rank within social hierarchies that reflect status and influence in society.1 It is well known that greater education is typically associated with higher social standing—a status consistently linked with better health outcomes. 4 The concept of subjective social status is particularly fascinating, i.e., an individual’s perception of their position in society. This subjective perception is a powerful predictor of your health status, even after accounting for measures of socioeconomic status like occupation, income, and education. 5,6 In other words, how you perceive your social standing can have a profound impact on your health, regardless of your socioeconomic circumstances.

Education - are you finding healthy friends?

Education not only provides you with the knowledge and skills to succeed academically, but also equips you with the resources to build and maintain strong social connections.

Education shapes the quality and extent of your social connections, which play a pivotal role in your overall well-being. Social networks serve as a vital source of both emotional and practical support, providing resources and comfort needed to navigate life's challenges.1

Higher levels of social support have been consistently linked with better physical and mental health outcomes. In fact, robust social networks are associated with lower rates of chronic diseases, reduced levels of stress, and improved overall well-being.7,8 Educated people tend to have larger and more supportive social networks.9,10 This suggests that education not only provides you with the knowledge and skills to succeed academically, but also equips you with the resources to build and maintain strong social connections. Whether it's offering a listening ear during times of need or providing practical assistance in times of crisis, these social advantages can significantly impact our health and well-being.

Education - building a future for your children

Children's academic success is closely linked to the educational background of their parents and the socioeconomic advantages that accompany it.

The story begins at home, where parental education plays a pivotal role in shaping children's educational journeys. Higher levels of parental education often translate into a supportive environment rich in resources and opportunities for learning. But the influence doesn't stop there. Parents' education also has far-reaching effects on the quality of schools their children are likely to attend.1 Educated parents typically have higher educational expectations for their children and may reside in areas with well-resourced schools.

The story begins at home, where parental education plays a pivotal role in shaping children's educational journeys. Higher levels of parental education often translate into a supportive environment rich in resources and opportunities for learning. But the influence doesn't stop there. Parents' education also has far-reaching effects on the quality of schools their children are likely to attend.1 Educated parents typically have higher educational expectations for their children and may reside in areas with well-resourced schools.

On a broader note, the education that your children achieve not only influences their own health as adults, but also the health of their future children.1 Thus, by participating in education, you are exerting a positive influence on the health outcomes of your children, grandchildren, and the generations to come. In doing so, you are perpetuating an intergenerational cycle of high educational attainment and optimal health among future generations.

Education, Employment & Income

Each additional year of schooling can result in an 11% increase in your income on average.

Higher levels of education increase your likelihood of obtaining employment in jobs characterized by healthier work conditions and better employment benefits. 1 Additionally, greater education often leads to higher-paying positions – an obvious bonus! Each additional year of schooling can result in an 11% increase in your income on average.11

Higher levels of education increase your likelihood of obtaining employment in jobs characterized by healthier work conditions and better employment benefits. 1 Additionally, greater education often leads to higher-paying positions – an obvious bonus! Each additional year of schooling can result in an 11% increase in your income on average.11

Jobs with higher salaries offer greater economic stability and more opportunities for wealth accumulation. This enables you to access healthcare, afford nutritious foods, and live in safer and healthier environments with supermarkets, parks, and places to exercise 12 – all of which promote good health by making it easier for you to adopt and maintain healthy behaviours. 1

The psychosocial aspects of work, including perceived fairness, discrimination, and social support among colleagues, play a significant role in shaping your health. Unfortunately, people with little education are more likely to encounter heightened psychosocial stress at work. 13,14 This can have both short- and long-term effects on health through stress-related pathways 1 and highlights the importance of addressing socioeconomic disparities within society. As a result, by pursuing higher education and striving for meaningful employment, you can not only enrich your life, but also pave the way for a healthier future for yourself and your community.

Education and Health Knowledge & Behaviours

People with higher levels of education are more likely to engage in health-promoting behaviours, such as maintaining a healthy diet, staying physically active, and avoiding smoking.

Education is a powerful tool that equips you with the knowledge, problem-solving abilities, and coping skills needed to make informed decisions about your health and the health of your loved ones.

Education is a powerful tool that equips you with the knowledge, problem-solving abilities, and coping skills needed to make informed decisions about your health and the health of your loved ones.

People with higher levels of education are more likely to engage in health-promoting behaviours, such as maintaining a healthy diet, staying physically active, and avoiding smoking. 15,16,17 This isn't just a coincidence - changes in health-related behaviours in response to new evidence, health advice, and public campaigns tend to occur earlier among more educated people.17,18

So how can we make education available to all?

With education having so many benefits for health, it seems obvious that post-secondary school education was almost free in the 1990s . If you'd be interested in working to make education almost free again, or better again totally free, you might consider working with us. As a first step, would you review our Anxiety and Action handbook here?

Bibliography

1 Egerter S, Braveman P, Sadegh-Nobari T, Grossman-Kahn R, Dekker M. Education matters for health. Exploring the social determinants of health: issue brief no. 6. Princeton (NJ): Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2011. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3863696/

2 Leganger, A., & Kraft, P. (2003). Control constructs: Do they mediate the relation between educational attainment and health behaviour?. Journal of health psychology, 8(3), 361-372. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591053030083006

3 Bailis, D. S., Segall, A., Mahon, M. J., Chipperfield, J. G., & Dunn, E. M. (2001). Perceived control in relation to socioeconomic and behavioral resources for health. Social science & medicine, 52(11), 1661-1676. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00280-X

4 Black D, Morris JN, Smith C, Townsend P, Whitehead M. Inequalities in Health. The Black Report: The Health Divide. London: Penguin Books; 1988.

5 Singh-Manoux, A., Adler, N. E., & Marmot, M. G. (2003). Subjective social status: its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Social science & medicine, 56(6), 1321-1333. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00131-4

6 Demakakos, P., Nazroo, J., Breeze, E., & Marmot, M. (2008). Socioeconomic status and health: the role of subjective social status. Social science & medicine, 67(2), 330-340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.038

7 Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban health, 78, 458-467. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/78.3.458

8 Brummett, B. H., Barefoot, J. C., Siegler, I. C., Clapp-Channing, N. E., Lytle, B. L., Bosworth, H. B., ... & Mark, D. B. (2001). Characteristics of socially isolated patients with coronary artery disease who are at elevated risk for mortality. Psychosomatic medicine, 63(2), 267-272.

9 Almeida, J., Molnar, B. E., Kawachi, I., & Subramanian, S. V. (2009). Ethnicity and nativity status as determinants of perceived social support: Testing the concept of familism. Social science & medicine, 68(10), 1852-1858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.029

10 Mickelson, K. D., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2003). Social distribution of social support: The mediating role of life events. American journal of community psychology, 32, 265-281. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:AJCP.0000004747.99099.7e

11 Rouse, C. E., & Barrow, L. (2006). US elementary and secondary schools: Equalizing opportunity or replicating the status quo?. The future of children, 99-123. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3844793

12 Almeida, D. M. (2005). Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Current directions in psychological science, 14(2), 64-68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00336.x

13 Almeida, D. M., Neupert, S. D., Banks, S. R., & Serido, J. (2005). Do daily stress processes account for socioeconomic health disparities?. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60(Special_Issue_2), S34-S39. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/60.Special_Issue_2.S34

14 Diez Roux, A. V., & Mair, C. (2010). Neighborhoods and health. Annals of the New York academy of sciences, 1186(1), 125-145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05333.x

15 Harper, S., & Lynch, J. (2007). Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in adult health behaviors among US states, 1990–2004. Public health reports, 122(2), 177-189. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490712200207

16 Kant, A. K., Graubard, B. I., & Kumanyika, S. K. (2007). Trends in black–white differentials in dietary intakes of US adults, 1971–2002. American journal of preventive medicine, 32(4), 264-272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.011

17 De Walque, D. (1940). Education, information, and smoking decisions: evidence from smoking histories, 1940-2000. Information, and Smoking Decisions: Evidence from Smoking Histories, 2000. https://ssrn.com/abstract=610405

18 Cutler D, Lleras-Muney A. (2006) Education and Health: Evaluating Theories and Evidence. Bethesda, MD: National Bureau of Economic